|

|

Part of the American

History & Genealogy Project |

Historic Old New York

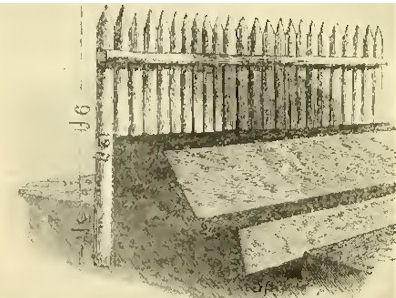

Wall Street

Section of City Wall, 1653

Today this name is synonymous with that

of speculation and great financial transactions. It is one of

the famous streets of the world, hut its name has no relation to

the business carried on in it. In 1653, during the reign of

Stuyvesant, when the Dutch were afraid of an attack from the

north, either by the Indians or by the English from the New

England colonies, a wall was built across the island to the

north of the city. It passed through what is now Wall Street,

thence to the Hudson River through the place where Trinity

church now stands.

The wall was a palisade made of posts

twelve feet in length and six inches in diameter; one end was

sharpened and the other set in the ground three feet deep. These

posts were set so close that they touched each other. Split

rails were spiked to the posts to strengthen the palisade.

Within the palisade was a sloping breastwork of earth four feet

high, three feet wide at the top and four feet at the bottom.

There were several semicircular bastions

along the line of the wall, one at East River, projecting into

the river so that the small cannon mounted on it could command

the river both up and down the stream. There was another bastion

near what is now Hanover Street, a third just west of William

Street, another where the sub-treasury building stands, and

still another just east of Broadway.

There was a gate in the wall near the

East River shore, and another at Broadway.

The wall was never used as a means of

defense. When it was torn down the street that was laid out

where the wall had been was not regarded as being one of much

consequence, but its importance was greatly increased when the

new City Hall was erected upon it, opposite Broad Street. The

erection of Trinity church at the head of this street added

greatly to its attractiveness. The first slave market in the

city was at the foot of Wall Street. The first library of the

city had its home in the City Hall. The famous Zenger trial was

held there. It was the City Hall, refurnished and improved, that

was renamed Federal Hall, and it was there that Washington took

the oath of office as President of the United States. It was in

this building that Congress held its sessions as long as New

York remained the capital of the nation.

Federal Hall

In 1770 a statue in honor of William

Pitt was erected in Wall Street, near the intersection of

William.

The Bank of New York, the first banking institution established

in the city, was located in Wall Street at the corner of

William. The next five banks established in New York were also

located in Wall Street.

The Jumel Mansion, 161st Street

In 1758 Roger Morris erected a mansion

for his wife, who was the daughter of Frederick Philipse, the

second lord of Philipse Manor. She was the beautiful and

cultured Mary Philipse who tradition says declined the hand of

Washington to marry Morris an aide-de-camp to Braddock. Morris

and his wife lived in this mansion till the beginning of the

Revolution, when, having sided with the royalists, their estate

was confiscated and the family went to England.

This famous old mansion is on 161st

Street near Edgecombe Road. Washington made this house his

headquarters after his retreat from Long Island, and when he was

compelled to abandon the city, General Knyphausen, the Hessian,

occupied it as his headquarters.

It was at this house that the

unfortunate Hale received his final instructions before starting

on his fatal errand, and here that Washington and his cabinet

were guests in 1790.

For some time after the Revolution the

title of the property was in dispute, but in 1810 John Jacob

Astor bought the claims of the Morris heirs. A little later the

house was sold to Stephen Jumel, an adventurous Frenchman who

settled in New York and became one of its leading merchants. He

married a beautiful New England girl and made the Morris mansion

his home. Jerome Bonaparte was a frequent guest of the Jumels,

and Louis Philippe, Lafayette, Talleyrand, and Louis Napoleon

were entertained by them.

Jumel died in 1832, and about a year

later his widow married Aaron Burr. The couple did not live

happily together. Burr squandered his wife's estate and when she

asked for an accounting coolly told her that that was not her

affair, that her husband could manage her estate. The couple

separated within a year from the time of their marriage, and for

thirty-one years after Mrs. Jumel lived in the old mansion,

spending the closing years of her life as a miser and a recluse.

During the time that John Jacob Astor

owned the place it is said that his friend and secretary,

Fitz-Greene Halleck, lived with him and wrote his famous poem

"Marco Bozzaris" in this historic old mansion. The house, which

has now most properly become public property, has not greatly

changed since the time it had for its guests Washington and many

other famous men.

Statue to Nathan Hale

Golden Hill

It was at Golden Hill, in John Street,

near William, that the first blood of the Revolution was shed.

Ever since the passage of the Stamp Act there had been bitter

feeling between the British soldiers and the Sons of Liberty.

The Liberty pole on the Common was made the rallying point of

the patriots, and because of this it was offensive to the

soldiers and was cut down by them. Twice it was replaced by the

Sons of Liberty, and twice cut down again by the soldiers. The

fourth pole was fastened with iron braces, and kept its place

till the night of the 16th of January, 1770, when a party of

soldiers not only cut it down for the fourth time, but cut it in

pieces, and piled the fragments in front of the headquarters of

the Sons of Liberty. This provoked the most intense anger. Two

days later there was a collision on Golden Hill and half a dozen

on each side were wounded; the next day the contest was renewed

and a sailor was killed by the soldiers. These two days'

fighting constitute what is known as the battle of Golden Hill.

This occurred six weeks before the massacre in King Street,

Boston, and five years before the Battle of Lexington, so New

York has reason for the claim made that in her streets was shed

the first blood in the cause of freedom.

The Bowery

Bowery, spelled bouwerie, is a Dutch

word for farm. The road that led through the various farms on

lower Manhattan Island was known as Bouwerie Lane and in time

became the street we now call the Bowery. Along this road grew

up a little hamlet, known as the Bowery. There was at this place

a famous tavern which was a favorite resort. It was here, in

1690, that the Commissioners from the New England colonies met

with those representing New York to consider plans for the

invasion of Canada.

For many years the Bowery was the only

road leading out from the little town clustered about Fort

Amsterdam.

The largest of the bouweries belonged to

Governor Stuyvesant; and it was on the Bowery road that he had

his country home. It was along this road that the post-rider

made his way in carrying the first mail from New York to Boston.

During the Revolution a large part of the British army in New

York was encamped along the Bowery, and the drinking places and

resorts for low grade entertainments that were established there

at that time drove the more fashionable people and the better

class of business to other parts of the city, and did much to

determine the future character of the street.

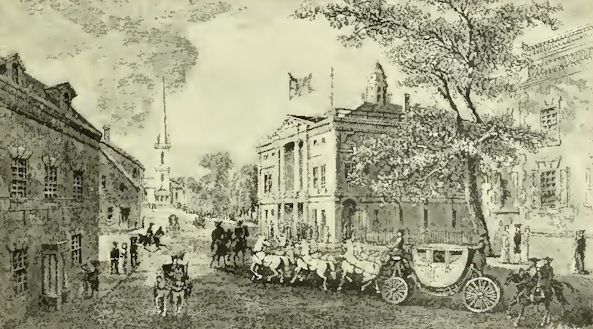

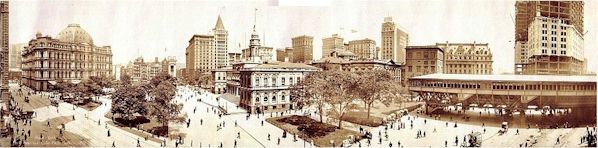

City Hall

City Hall, Park Row and City Hall Park, 1911

The new City Hall on the corner of Wall

and Nassau Streets, completed in 1700, was a very fine building

for the time. It contained the only prison in the city till

1760, so it must have been here that Zenger was confined during

the imprisonment preceding his trial for libel. It was here that

the Stamp Act congress assembled here that the chief men of the

town met and resolved that they would not pay the tax on tea;

here that the Sons of Liberty came and confiscated the arms and

ammunition stored in one of the rooms, after they had heard the

news from Concord and Lexington. It was from the balcony of the

City Hall that the Declaration of Independence was read, by

order of Congress. It was on the site of this famous City Hall

that the United States Sub-Treasury building was erected.

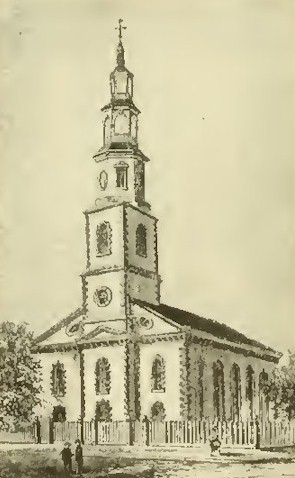

Trinity Church

A Royal grant of land was given to

Trinity in 1697, and the first church erected upon it was

occupied in 1698. This church was destroyed by the great fire of

1776, and was rebuilt in 1778. The present edifice was erected

in 1846. In 1703 the church came into the possession of what was

known as the "King's Farm" which has since been a source of

princely revenue to Trinity. Many churches and parishes owe

their existence to the funds derived from this source. King's

College, now Columbia University, owes its organization to the

same means. All the income from the great estate, which in the

early days was the Annetje Jans farm, is used for the support of

Trinity, and several other churches in the city; in aiding weak

churches in other places; in maintaining hospitals; in providing

scholarships at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., and for many

other beneficent purposes.

William Vesey, in whose honor Vesey

Street was named, was the first rector of Trinity and served in

that capacity for nearly fifty-years. It is quite remarkable

that in the more than two hundred years of its existence Trinity

has had only nine rectors.

In Trinity Churchyard are the remains of

many noted men. Here lie William Bradford, editor of the first

newspaper in New York; Sir Henry Moore, Sir Danvers Osborne, and

James DeLancey. colonial governors; Robert Livingston; Michael

Cresap, a noted Indian fighter; Alexander Hamilton and Albert

Gallatin, famous Secretaries of the Treasury; the Earl of

Sterling; John Iamb, and Marius Willett, the founders and

leaders of the Sons of Liberty; Philip Livingston and Robert

Lewis, signers of the Declaration of Independence; Robert

Fulton; General Phil. Kearney; Charlotte Temple; James Lawrence,

and many others but little less noted.

The Battery

When the English came into the

possession of the city they proceeded to strengthen the fort by

the erection of batteries. In course of time both the fort and

the associated batteries fell into disuse, and when they were

finally removed, a considerable portion of the territory was

made into a park which is still known as the Battery. It was

here that Lafayette landed on his visit to this country in 1824.

It was here, in Castle Garden, that a grand reception was given

him. It was here that Clay and Webster were heard; here that

Jackson and other Presidents were received; here that Kossuth

was welcomed, and Jenny Lind sang; here that Mario, Grisi, and

many others were heard. But with the opening of the Academy of

Music in Fourteenth Street in 1854 the day of Castle Garden as

the home of the opera came to an end. The following year it

became a landing place for immigrants and continued to be used

for that purpose till 1890, since which time it has been under

the jurisdiction of the department of public parks and used as

the home of the New York Aquarium.

In former years the Battery Park had

been the strolling place of Generals Howe and Clinton; of

Washington, Arnold, and Andre; of Jefferson, Burr, and Hamilton;

of Jerome Bonaparte, and Louis Philippe; of Irving, Cooper,

Halleck, Drake, Willis, and Morris.

Bowling Green

A small park at the foot of Broadway

that has always been used for public purposes is known as

Bowling Green. When Fort Amsterdam was built the open space to

the north of it was left for a public common, then known as "The

Plaine." It is probable that it was on or near this spot that

Minuit met with the Indians to bargain for Manhattan Island.

This little park in the early days was the village green and the

children's playground. It was here that Governor Kieft

established two annual fairs, one held in October and the other

in November. It was here that the "May-Day" festivals were held.

After a time this plot of ground came to

be known as "The Parade." In 1732 the city fathers leased it to

John Chambers. Peter Bayard, and Peter Jay, who prepared it for

playing the game of bowls, whence the more modern name of the

park. On the 2 1st of August, 1770, a leaden statue of George

the Third was erected in the centre of Bowling Green. Just at

the breaking out of the Revolution the statue was torn down and

sent to Litchfield, Connecticut, where the wife and daughter of

Governor Wolcott made forty-two thousand bullets from it.

Fraunces' Tavern

This historic building, one of the

oldest in the city, is at the corner of Pearl and Broad Streets.

It was built in 1730 by Stephen DeLancey, a Huguenot nobleman

who fled from France. The firm of DeLancey, Robinson, and

Company occupied the old mansion as a store from 1757 to 1761.

In January, 1762, the property passed into the hands of Samuel

Fraunces, a West Indian, who used it as a tavern. It was for

many years the most popular place in the city, the Delmonico of

its time.

It was the favorite meeting place of

"The Moot," a club composed mainly of lawyers, and which

included in its membership such names as Livingston, Jay,

DeLancey, and Morris. Here also met the "Social Club" having

among its members John Jay, Gouverneur Morris, Robert

Livingston, Morgan Lewis, and Gulian Verplanck. It was at

Fraunces' tavern that the Board of Trade of New York City was

organized. The British held dancing assemblies there during

their occupancy of the city. It was there that Governor Clinton

gave a dinner to Washington and other noted men when the

Americans entered the city after it was evacuated by the

British. It was there that Washington, ten days later, at noon

on the 4th of December, 1783, in the famous "Long Room" bade

farewell to his associates in the army.

The Beekman House 1860

A house of much historic interest

formerly stood on Fifty-First Street. At the time of the

Revolution it was occupied by James Beekman. Being a loyalist

Beekman fled when Washington entered the city after the Battle

of Long Island. When Sir William Howe was in New York he made

this house his headquarters. It was here that Andre received his

final instructions before going to meet Arnold; here that Nathan

Hale was tried and condemned to be hanged. When Washington was

President, and living in New York, he often stopped at this

house while driving about the city.

The Philipse Manor House

Although this house was not in the city

of New York its owner and occupant was a part of the city life,

and active in all the affairs that had to do with the city's

welfare. The older part of the house was built in 1682, and the

newer part in 1745. The building as a whole is a curious mixture

of Dutch and English architecture. It was built by Frederick

Philipse, who came to this country a penniless youth of high

birth in the time of Stuyvesant. He engaged in the fur trade and

became the richest man in the colony. His property, together

with that of many other wealthy loyalists, was confiscated after

the Revolution.

The beautiful Mary Philipse, with whom

it is said Washington was deeply in love, lived at the Philipse

Manor House. In 1868 the city of Yonkers bought the Manor House

and converted it into a City Hall.

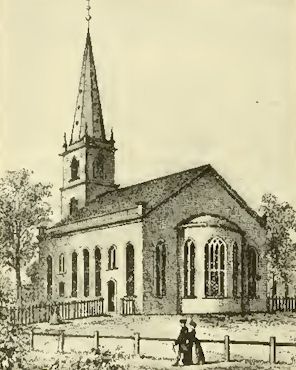

St. George's Chapel

St. George's Chapel stood on the corner

of Cliff and Beekman Streets and was for many reasons a

structure of much interest. It was erected as a chapel by

Trinity Church but later became a separate organization. The

demands of business led to its removal in 1868 and a new

building was erected in Sixteenth Street. The lot on which the

old church stood was purchased in 1748 for $500. It is probably

worth more than a million dollars now. The first subscription

for the church was made by Sir Peter Warren who gave £100 and

asked that a pew be reserved for himself and family in

perpetuity. The installation services were held on the 1st of

July, 1752. St. George's was burned in January, 1814, but was

rebuilt on the same walls. It is said that Washington frequently

attended service here during the early part of the Revolution.

Among the members of St. George's were the Schuylers,

Livingstons, Beekmans, Van Rensselaers, Van Courtlandts, Reades,

Moores and other famous families.

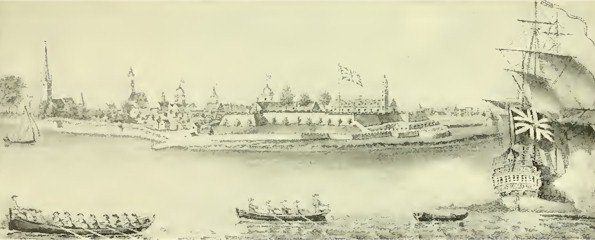

Fort George and City of New York, 1740

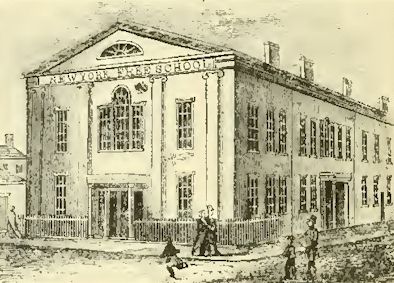

Early Schools

Something has already been said of

education under the Dutch and that upon the coming of the

English interest in education languished. It was not until a

considerable time after the close of the Revolution that much

interest was manifested in public education. In 1805 a society

was formed which in 1808 took the name of "Free School Society

of the City of New York." The first building which they erected

was dedicated on the 11th of December. 1805. The dedicatory

address was given by De Witt Clinton, who said the purpose of

the society was not "the founding of a single academy, but the

establishment of schools." By 1825 the society had erected six

school buildings. The first school building was two stories in

height, built of brick, and would accommodate six hundred and

fifty pupils.

First Free School Building In New York

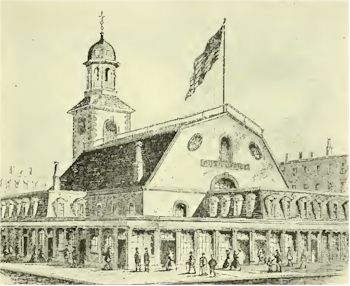

The Middle Dutch Church

Old Post office, Formerly Middle Dutch Church

This church was situated on Nassau

Street. Between Cedar and Liberty Streets. It was finished in

1731, and was in the fullest sense a Dutch church. The English

language was not used in preaching in it till 1764. The church

would seat about twelve hundred people, and its congregation was

the largest in the city. This church was for a long time

regarded as one of the finest buildings in the city.

During the Revolution it was used as a

military prison. It had to be thoroughly repaired afterwards and

was not reopened for service after the Revolution till 1790. In

1845 it was leased to the United States Government, and used as

a post office for thirty years.

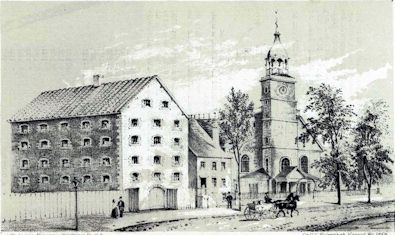

Old Sugar House in Liberty Street

The Old Sugar House in Liberty Street

was used as a prison during the Revolution. More than eight

hundred of the patriots were confined there at one time. They

had almost no bedding and absolutely no fire, during one of the

coldest winters ever known in the city, so cold that for forty

days the Hudson River was frozen over between Cortlandt Street

and the New Jersey shore, as far down as Staten Island. There

were no windows in the building, and the food furnished was poor

and insufficient, "a loaf of bread, a quart of peas, half a pint

of rice, and one and a half pounds of pork for six days." Many

died of want.

AHGP New York

Source: Stories from Early New York

History, by Sherman Williams, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons,

1906

|