|

|

Part of the American

History & Genealogy Project |

The Battery, New York

The Fort and Battery, 1750

When Hendrick Hudson came sailing into

the mouth of the river that thenceforward was to be known by his

name, on that September day in the year 1609, almost the whole

of what now is called "the Battery" was under water at high

tide. And it is a fact, notwithstanding the thundering of guns

which has gone on thereabouts, and the blustering name that the

locality has worn for more than two centuries, that not a single

one of New York's enemies ever would have been a whit the worse

had the tides continued until this very moment to cover the

Battery twice a day! Actually, the entire record of this

theoretically offensive institution, whereof the essential and

menacing purpose, of course, was that somebody or something

should be battered by it, has been an aggregation of gentle

civilities which would have done credit to a rather

exceptionally mild-mannered lamb.

Most appropriately, this affable

offspring of Bellona came into existence as the friendly prop to

a still more weak-kneed fort. For reasons best known to

themselves, the Dutch clapped down what they intended should be

the main defense of this island upon a spot where a fort, save

as a place of refuge against the assaults of savages, was no

more than a bit of military bric-a-brac. Against the savages it

did, on at least one occasion, serve its purpose; yet had even

these attacked it resolutely they must surely have carried it:

since each of the Dutch governors has left upon record bitter

complaining of the way in which it was invaded constantly by

cows and goats who triumphantly marched up its earthen ramparts

in nibbling enjoyment of its growth of grass. When the stress of

real war came, with the landing of the English forces in the

year 1664, the taking of this absurd fort was a mere bit of

bellicose etiquette: a polite changing of garrisons, of fealty,

and of flags.

Later, when Governor Stuyvesant very

properly was hauled over the coals for the light-handed way in

which he had relinquished a valuable possession, his explanation

did not put the matter in much better shape. "The Fort," he

wrote, "is situated in an untenable place, where it was located

on the first discovery of New Netherland, for the purpo.se of

resisting an attack of the barbarians rather than an assault of

European arms; having, within pistol-shot on the north and

southeast sides, higher ground than that on which it stands, so

that, notwithstanding the walls and works are raised highest on

that side, people standing and walking on that high ground can

see the soles of the feet of those on the esplanades and

bastions of the Fort."

Having themselves so easily captured it,

the English perceived the need of doing something to the Fort

that would enable them to hold it against the Dutch in the

probable event of these last trying to win it back again. The

radical course of abandoning it to the cows and goats and

building a new fort upon higher ground, on, for instance, the

high bluff above the river-side where Trinity Church now stands,

would have been the wisest action that could have been taken in

the premises; but the very human tendency to try to improve an

existing bad thing, rather than to create a new good thing,

restrained them from following out this one possible line of

effectual reform. Raising the walls of the Fort was talked about

for a while; until Colonel Cartwright, the engineer, put a

stopper upon this suggestion by declaring, in effect, that

taking the walls up to the height of those of Jericho would not

make the place tenable. And then, after more talk, the decision

was reached that to build a battery under the walls of the Fort

would be to create defenses "of greater advantage and more

considerable than the Fort itself": whereupon this work was

taken in hand by General Leverett and carried briskly to

completion and from that time onward the Battery has been part

and parcel of New York.

The amount of land which then

constituted the Battery was trifling: as is shown by the

statement in Governor Dongan's report to the Board of Trade

(1687), "the ground that the Fort stands upon and that belongs

to it contains in quantity about two acres or thereabouts." The

high-water mark of that period would be indicated roughly by a

line drawn with a slight curve to the westward from the foot of

the present Greenwich Street to the intersection of the present

Whitehall and Water streets. All outside of this line is made

land which has been won from the river, the greater part of it

within the past forty years, by filling in over the rocks which

fringed this southwestern shore.

This primitive Battery was but a small

affair, loosely constructed and lightly armed. As to its

armament, the report of the survey ordered in the year 1688

contains the item : "Out the Fort, under the flag-mount, near

the water-side, 5 demi culverins;" and its inherent structural

weakness is shown by the fact that only five years after its

erection-that is to say, in 1689, when Leisler's righteous

revolt made the need for strong defenses urgent, its condition

was so ruinous as to be beyond repair; wherefore it was replaced

by "a half-moon mounting seven great guns."

As the event proved, this half-moonful

of guns would have satisfied for almost another century all that

might have been (but was not) required of artillery in this

neighborhood. But the times were troublous across seas; and the

Leisler matter had proved that questions of European abstract

faith and concrete loyalty might exercise a very tumultuous and

dismal influence upon American lives. And so the prudent New

Yorkers, about the year 1693, decided to bring their waterside

defenses to a condition of high efficiency by building "a great

battery of fifty guns on the outmost point of rocks under the

Fort, so situated as to command both rivers," and, incidentally,

to defy the world.

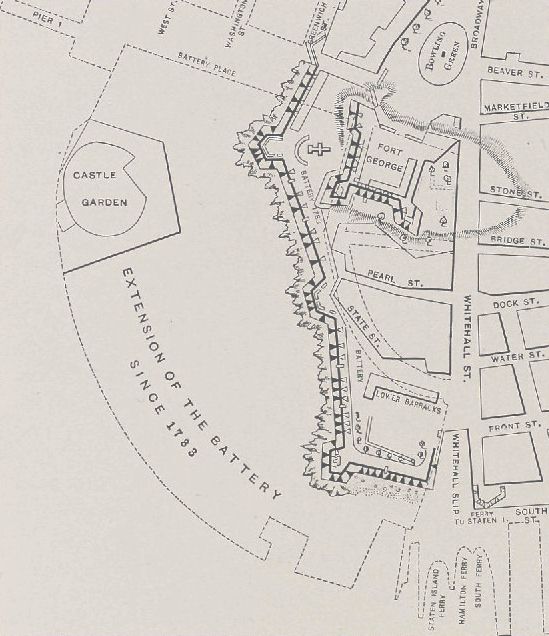

Extension of the Battery Since 1783

In the mere planning of this nobly

defiant undertaking there seems to have been gained so

comforting a sense of security that its realization was not

arrived at for nearly half a century, as appears from Governor

Clarke's statement (1738): "There is a battery which commands

the mouth of the harbor, whereon may be mounted 50 cannon. This

is new, having been built but three years, but it wants

finishing." In the course of the ensuing thirty years, possibly

even sooner, the finishing touches seem to have been supplied;

at least, the Battery is shown as completed on Ratzen's map of

1767; and it is certain that these defenses were in effective

condition while New York was held by the English during the

Revolutionary War. Indeed, during the Revolutionary period the

Battery really was a battery of some importance: as may be seen

by the accompanying plan, showing a line of works extending from

the foot of Greenwich Street along all the water-front to

Whitehall Slip. But what made the Battery harmless at that,

potentially, most belligerent period of its history was

precisely what has made it harmless throughout the whole of its

kindly career: the absolute absence of an enemy at whom to

discharge its guns.

When the Revolutionary War was ended the

nonsensical Fort at last was demolished, which was good riddance

to amusingly bad rubbish and with it the Battery went too. Why

this last was razed is not at all clear. Unlike the Fort, it was

not in anybody's way, and it was not a military laughing-stock.

On the contrary, it occupied an otherwise unused corner of the

island, and so well commanded the entrance to the East and North

rivers that it was saved from being deadly dangerous only by the

persistent absence of a foe. Indeed, in theory, at least, it was

so reasonable a bit of fortification that when we went to

fighting England again, in the year 1812, it immediately was

built up anew. During that period of warfare, of course, nothing

more murderous than blank cartridge was fired from its eager

guns; but there it was, waiting with its usual energy for the

chance to hurt somebody which (also as usual) never came.

Meanwhile there had been set up in this

region another military engine of destruction which, adapting

itself to the gentler traditions of its environment, never came

to blows with anybody, but led always a life of peaceful

usefulness that is not yet at an end. This was the Southwest

Battery: that later was to be known honorably as Castle Clinton;

that still later was to become notable, and then notorious, as

Castle Garden; and that at the present time is about to take a

fresh start in respectability as the Aquarium.

It is not easy to realize, nowadays, as

we see this chunky little fort standing on dry ground, with a

long sweep of tree-grown park in its rear, that when it was

built, between the years 1807 and 1811, it was a good hundred

yards out from the shore. Its site, ceded by the city to the

Federal Government, was a part of the outlying reef known as

"the Capske" and when the fort was finished the approach to it

was by way of a long bridge in which there was a draw. The

armament of this stronghold was twenty-eight 32-pounders: and

when these went banging off their blank-cartridges in salutes,

and clouds of powder-smoke went rolling down to leeward, there

was not a more pugnacious-looking little fume of a fort to be

found in all Christendom.

The Battery Park, or Battery Walk, as it

indifferently was called, of that period was a crescent shaped

piece of ground of about ten acres, being less than half the

size of the Battery Park of the present day, which ended at the

water-side in a little bluff, capped by a wooden fence, with a

shingly beach beyond. Along the edge of the bluff the earthworks

of the year 1812 were erected, and were neither more nor less

useful than the wooden fence which they replaced. However, what

with the grim array of guns lowering over the earthen parapet,

and the defiant look of the obese little fort, the New York of

that epoch mu.st have worn to persons approaching it from the

seaward, being for the most part oystermen and the crews of

Jersey market-boats, a most alarmingly swaggering and dare-devil

sort of an air.

The Battery, 1822

Yet was there a cheerful silver lining

to these dismally black clouds of war. In his admirable

monograph upon " New York City during the War of 1812-15," Mr.

Guernsey writes: "In the summer of 1812 there was occasionally

music after supper, at about 6:30 P.M., at the Battery

flagstaff," which " stood at the southeast end of the Battery

parade, and was surrounded by an octagon enclosure of boards,

with seats inside and a roof to shelter from the weather.

Refreshments and drinks were served from this building, and a

large flag was displayed from the pole at appropriate times."

Never, surely, was there a more charming exhibition of combined

gentleness and strength than then was made: when the brave men

of New York, night after night, gallantly invited the beautiful

women their fellow-citizens to partake of "refreshments and

drinks" close beside the stern rows of deadly cannon, and

beneath the flag to defend which, as the women themselves, they

were sworn! In all history there is no parallel to it: unless,

perhaps, it might be likened to the ball and the battle of

Waterloo, with the battle left out.

Even the New-Yorkers of that period,

whose infusion of Dutch blood still was too strong to permit

them easily to assimilate ideas, could not but perceive that as

a place of recreation, where refreshments and drinks could be

had to a musical accompaniment, the real use of their

pseudo-Battery at last had been found. Out of this rational view

of the situation came the project, formulated soon after Castle

Clinton was receded to the city, in the year 1822, upon the

translation of the Federal military headquarters to Governor's

Island, to make over the fort into a place of amusement; which

project was realized, and Castle Garden came into existence, in

the year 1824. From that time onward, through all the phases of

its variegated career, as concert-hall, place of civic assembly,

theatre, immigrant depot, armory, the building at least has been

able to account for itself on grounds whereof the mere statement

would not, as in the days when it was pretending to be a fort,

instantly excite a grin.

With the departure from Castle Clinton

of the last of its 32-pounders went also the last vestige of an

excuse on the part of the Battery for retaining its Sir Lucius

O'Trigger of a name. But in that region, fortunately, old names

live on. There are the Beaver's Path and the Maiden's Lane, the

first of which has ceased to be the exclusive property of

beavers, and the second of maidens, for more than two and a half

centuries; there is the Wall Street, whence the wall departed

about A.D. 1700; and there is the Bowling Green, where bowls

have not been played for well on toward two hundred years. With

these admirable precedents to stay and to strengthen it in use,

there is no fear that the name of the Battery soon will pass

away. And even should the brave name be lost in the course of

ages, still, surely, must be preserved always the gracious

legend of those peaceful guns which never thundered at a foe.

AHGP New York

Source: Stories from Early New York

History, by Sherman Williams, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons,

1906

|