|

|

Part of the American

History & Genealogy Project |

West Point and the Lower Hudson

Securing the control of the Hudson River

was a favorite project with the British as its possession would

enable them to cut the colonies in twain and subdue each section

in turn. Not only would the control of the Hudson enable them to

open a road to Montreal and so cut off the New England colonies,

but once in possession of Albany they would easily overrun the

Mohawk valley, give encouragement to the many Tories there, and

be in close touch with their Indian allies, the Iroquois.

The Americans were as anxious to prevent

the control of the Hudson by the British, as the latter were to

secure it. After extended investigation it was decided that West

Point offered the best location for defensive works. The river

was very narrow there, not much over fourteen hundred feet wide

; the banks were high ; mountains overlooking the river on all

sides ; and at this point the river bent almost at right angles

so that cannon would control for a long distance, and

obstructions to navigation could easily be placed and

maintained. Beside all these advantages there was a high, rocky

island in the river just above West Point that could be

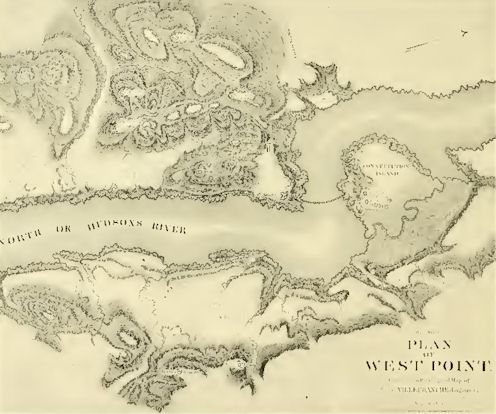

fortified readily. The plan of West Point below makes the

situation clear.

Plan of West Point

The occupation of West Point by the

Americans was a constant menace to New York, therefore the

British had a double reason for desiring possession of the

Hudson. The struggle for West Point enabled Arnold to carry into

effect the treasonable purposes he had for some time

entertained. There is in all American history no sadder incident

than that of Arnold's treachery. A strong, brave man, who had

made a fine record as a soldier, by a single act destroyed for

all time all the esteem in which he had been held. While the

treason of Arnold can never be forgotten nor condoned, one

cannot forget the part he took at Quebec, and at Saratoga, nor

can one overlook the fact that he was not always treated fairly.

Benedict Arnold was a descendant, and

namesake, of one of the early governors of Rhode Island. Young

Arnold began business as an apothecary, and later added to his

enterprise the selling of books and stationery. At the outbreak

of the Revolution he marched to Cambridge in the command of a

company. He was with Allen at Ticonderoga, and wherever he was

he was in the thickest of the fight. By many he was regarded as

the hero of Saratoga.

Arnold was not advanced as rapidly as he

felt he should be, and on several occasions he was deeply

humiliated, but had there not been a lack in his character,

somewhere, we should not now have to tell the story of his

treason. While Arnold was at Philadelphia he married Margaret

Shippen, a daughter of one of the Tory residents of the city.

Arnold, who was always fond of display, lived far beyond his

means at this time. He kept a coach, servants in livery, gave

splendid banquets, and in such ways incurred debts that he could

not meet. He was accused of raising money in improper ways, and

on being tried was acquitted on two charges, but found to be

guilty in some measure on others. A part of the court before

whom he was tried voted to cashier him, but the majority decided

that he should be reprimanded by his Commander-in-Chief.

Washington performed this duty with all possible delicacy, for

he had always been a friend of Arnold's, and he did not believe

there had been any wrong intent. This was the condition of

affairs that existed when Arnold sought the command at West

Point, which Washington gladly gave him. Even at this time

Arnold had been in treasonable correspondence with the British.

The picture is the blacker because Arnold sought this position

that he might betray not only his country, against which lie

thought he had grievances, but his commander as well, who had

always been his friend, and who had done all that he could to

shield him from criticism, and to promote his interests.

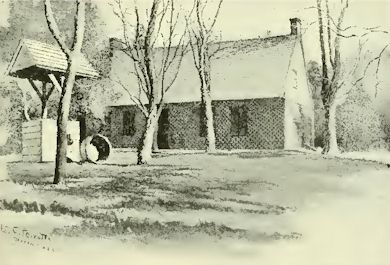

While at West Point Arnold occupied as

his headquarters the Beverley Robinson House, which was situated

on the east bank of the Hudson, nearly opposite West Point, and

at the foot of Sugar Loaf Mountain. The house was built about

1750 by Colonel Beverley Robinson, son of John Robinson,

President of the colony of Virginia. The grounds contained about

a thousand acres. The estate came to Robinson through his wife,

a daughter of Frederick Philipse. During the Revolution Robinson

sided with the British and raised a regiment of loyalists for

the British service. At the close of the war his estate was

confiscated. The house was destroyed by fire in 1892, being at

that time the property of Hamilton Fish. Washington was at this

house frequently, and Putnam and other American officers made

their headquarters there. It was at this house that Washington

had the sad interview with the almost distracted Mrs. Arnold

after the discovery of the treason of her husband. It was to

this house that Roger Morris and his wife came when they were

obliged to flee from New York when that city was occupied by the

American troops. It was at this house that Hamilton and

Lafayette were at dinner when they received the dispatch

announcing the capture of Major Andre.

The Beverley Robinson House

André

A correspondence had been carried on

between Andre and Arnold for some time, Andre writing over the

signature John Anderson, while Arnold signed himself "Gustavus."

It became necessary to have a meeting between Arnold and someone

who could speak for Sir Henry Clinton with authority. Major

Andre was chosen to act in that capacity. It was at first

planned to have the meeting take place at Dobb's Ferry, and

Arnold went down the river in his barge for that purpose, but

owing to some misunderstanding his boat was fired upon and he

was compelled to withdraw. He returned to West Point, and Andre,

who was at Dobb's Ferry, went back to New York.

The first effort to bring about a

meeting had resulted in failure. There was further

correspondence, after which Andre went up the river as far as

Teller's Point, where, on board the Vulture, he waited until a

meeting with Arnold could be arranged. Arnold was aided in this

matter by Joshua Hett Smith, who lived on the west side of the

river, about two and a half miles below Stony Point. His house

has long been known as the "Treason House," because Arnold and

Andre met there and arranged their plans for the surrender of

West Point. To what extent Smith was in the confidence of Arnold

will probably never be known. Whether Smith was a Tory, or

whether he was deceived by Arnold, will always be a matter of

some doubt.

On Thursday, the 21st of September,

1780, at about midnight, Smith, with two of his tenants acting

as boatmen, rowed out to the Vulture. Andre was brought ashore

and met Arnold about two miles below Haverstraw, at the foot of

Long Clove Mountain. The two men talked together till morning,

when, not having completed their plans, they went to Smith's

house, Andre going very reluctantly. As they reached the house

they heard the sound of cannonading. Colonel Livingston, who was

in command at Verplancks Point, had opened fire on the Vulture,

which he compelled to drop down the river. Arnold and Andre

remained in consultation nearly all day. At the close of their

conference Arnold returned to the Robinson House in his barge,

having given passports to Andre which would enable him to pass

the American lines at that point.

Arnold's movements caused no suspicion

as he had accounted for them in advance in a very plausible way.

Treason House

The Vulture, after having been driven

down the river, returned and waited for Andre, but Smith for

some reason would not row him out to the vessel. Being compelled

to attempt his return by land Andre, with Smith for a guide, set

out on horseback a little before, sunset. Andre changed his

military suit for citizen's clothes which Smith furnished. They

went up the river as far as King's Ferry, where they crossed

over to Verplancks Point. From this point they went to Compound,

where they were stopped by a sentinel who insisted upon seeing

their pass. They remained over night with one Andreas Miller and

set out early in the morning, taking the road to Pine Bridge.

When within two miles of this place they stopped and took

breakfast with a Mrs. Sarah Underhill. Here Smith left and

hastened back to the Robinson House to report Andre's movements

to Arnold.

It had been planned to have Andre go

from Pine's Bridge to White Plains, but he heard such reports as

to the safety of the route that he changed and took the road to

Tarrytown instead. When near the latter place he was halted by

three men, John Paulding, David Williams and Isaac Van Wart. The

following quotations from the testimony which these men gave

later is of interest. Paulding said:

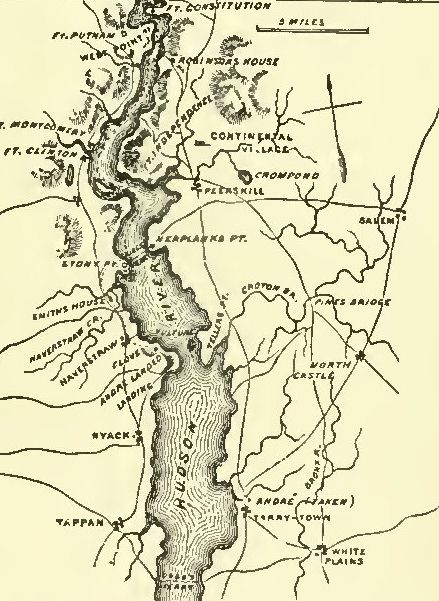

Movements of Arnold and Andre

"Myself, Isaac Van Wart and David

Williams were lying by the side of the road about half a mile

above Tarrytown, and about fifteen miles above Kingsbridge, on

Saturday morning, between nine and ten o'clock, the 23rd of

September. We had lain there about an hour and a half, as near

as I can recollect, and saw several persons we were acquainted

with whom we let pass. Presently, one of the young men who were

with me said, 'There comes a gentleman-like looking man, who

appears to be well dressed, and he has boots on, and you better

step out and stop him, if you do not know him.' On that I got up

and told him to stand, and then asked which way he was going.

Then he said, 'I am a British officer, out in the country on

particular business, and I hope you will not detain me a

minute,' and to show that he was a British officer he pulled out

his watch. Upon which I told him to dismount. He then said, 'My

God! I must do anything to get along,' and seemed to make a kind

of a laugh of it and pulled out General Arnold's pass, which was

to John Anderson to pass all guards to White Plains and below.

Upon that he dismounted. Said he, 'Gentlemen, you had best let

me go, or you will bring yourselves into trouble, for your

stopping me will detain the general's business;'" and he said he

was going to Dobb's Ferry to meet a person there and get

intelligence for General Arnold. Upon that I told him I hoped he

would not be offended; that we did not mean to take anything

from him: and I told him there were many bad people on the road,

and I did not know but perhaps he might be one."

Williams gave the following testimony:

"We took him into the bushes and ordered him to pull off his

clothes, which he did; but, on searching him narrowly, we could

not find any sort of writings. We told him to pull oft' his

boots, which he seemed to be indifferent about; but we got one

boot oft' and searched in that boot and could find nothing. But

we found that there were some papers in the bottom of his

stocking next to his foot; on which we made him pull his

stocking oft, and found three papers wrapped up. Mr. Paulding

looked at the contents and said he was a spy. We then made him

pull oft' his other boot, where we found three more papers at

the bottom of his foot within his stocking. Upon this we made

him dress himself, and I asked him what he would give us to let

him go.

He said he would give us any sum of

money. I asked him whether he would give his horse, saddle,

bridle, watch, and one hundred guineas. He said 'Yes,' and told

us he would direct them to any place, even if it were that very

spot, so that we could get them. I asked him whether he would

not give us more. He said he would give us any quantity of dry

goods, or any sum of money, and bring it to any place we might

pitch upon, so that we might get it. Mr. Paulding answered, 'No,

if you would give us ten thousand guineas you should not stir

one step.' I then asked the person who had called himself John

Anderson if he would not get away if it lay in his power. He

answered, 'Yes, I would.' I told him I did not intend he should.

While taking him along we asked him a few questions and we

stopped under the shade. He begged us not to ask him questions

and said when he came to any commander he would reveal all."

The papers found on Andre showed the

number and the distribution of the troops at West Point, the

positions they would occupy in case of an attack, the location

of the different forts and batteries, with the men and guns for

the defense of each, and all such other information as an enemy

would desire to have. Arnold agreed that in case an attack was

made on West Point he would scatter the forces and so arrange in

other ways that no effective defense could be made.

Andre was taken to North Castle, the

nearest military post, and turned over to the commander,

Lieutenant-Colonel Jameson, who, unaccountable as it may seem,

after reading the papers found on Andre, decided to send him to

Arnold in charge of Lieutenant Allen. He did so, writing a

letter to Arnold, saying that he had sent the captured papers to

Washington. Soon after Andre left Major Tallmadge, the second in

command at North Castle, learned what had been done. He declared

that he was suspicious of Arnold and urged that Andre be brought

back. To this Jameson gave a reluctant consent. The next day

Major Tallmadge took Andre to Lower Salem and left him in charge

of Lieutenant King. From here Andre was sent to the Robinson

House, then to West Point, and from there to Tappan, where he

was confined till his trial. General Washington had been at West

Point only a short time before the meeting of Arnold with Andre.

He had gone on to Hartford and was to stop at West Point on his

return from that place. He was back at West Point on the 24th of

September, the day that the British had been expected to make

their attack, for the scope of Arnold's treason contemplated the

capture of Washington as well as West Point.

Washington returned from Hartford by the

way of Fishkill. Soon after leaving the latter place he met the

French Minister, Luzerne, with his suite, and was persuaded to

return with them in Fishkill and spend the night there. Early

the following morning Washington and his staff were on their way

to West Point, intending to breakfast with Arnold at the

Robinson House, but as they approached the place Washington took

another road, and Lafayette said, "General, you are going in the

wrong direction." Washington replied humorously. "Ah, I know,

you young men are all in love with Mrs. Arnold, and wish to get

where she is as soon as possible. You may go and take your

breakfast with her and tell her not to wait for me, for I must

ride down and examine the redoubts on this side of the river,

and will be there in a short time." However, the officers

accompanied Washington, with the exception of two aids, who, at

the request of Washington, rode on to notify Mrs. Arnold of the

cause of the delay.

Breakfast was waiting when the aids

arrived, and those present sat down. During the meal a letter

from Colonel Jameson was handed to Arnold. It was the one

Jameson wrote two days before, announcing the capture of Andre.

Arnold asked to be excused, saying he was needed at West Point

immediately. To his aids he said, "Say to General Washington

that I have unexpectedly been called over the river and will

return very soon." He went to his wife's room and sent for her.

Lie told her that he must leave at once, and that they might

never meet again, that his life depended upon his reaching the

British lines before he was detected. Mrs. Arnold fainted.

Leaving her in that condition Arnold hurried down stairs,

mounted a horse and rode at full speed to the bank of the river,

where his boat lay. He entered it and directed the men to row

rapidly down the river, telling them that he was going on board

the Vulture with a flag of truce, and that he was in great

haste, as he was expecting Washington and wished to return as

soon as possible.

Washington arrived at the Robinson House

just after Arnold left. He received Arnold's message, took a

hasty breakfast, and went over to West Point to meet him, and

was greatly surprised to find that Arnold was not there, and had

not been for two days, and that the officer in charge had not

heard from him in that time. Washington inspected the works and

returned to Arnold's for dinner. As he was walking up from the

dock he met Hamilton, who told him of Arnold's treason and

flight. Calling upon Knox and Lafayette for counsel, Washington

said. "Whom can we trust now?" Hamilton was sent immediately to

Verplanck's Point in the hope of intercepting Arnold, but the

traitor was already on board the Vulture.

Washington's Headquarters at Tappan

Washington could not know whether or not

others were involved in Arnold's treason, but he decided to take

all the officers into his confidence. This was greatly

appreciated by them, the more so because circumstances were

somewhat against Jameson, and one "or two others, though all

were innocent of any wrong act.

Andre did not seem to fear death

greatly, but he dreaded to die the death of a spy, and begged

that he might be shot instead of being hanged. Every one

sympathized with him, but it seemed necessary that an example

should be made of him, the more so that his case was very

similar to that of Hale, for whom no mercy had been shown.

Capture of Major André

At Tappan André was confined in a stone

mansion, afterward occupied as a tavern by Thomas Wandle. His

trial took place in the old Dutch church.

The Americans made strenuous efforts to

capture Arnold, but without avail, General Clinton and other

British officers pleaded earnestly for Andre's release, which of

course could not be granted. Arnold wrote a letter to Washington

threatening in case Andre was executed to retaliate upon every

American whom he might afterward capture. Arnold's course after

his treason did quite as much toward blackening his memory as

did his treason itself.

André was arrested near Tarrytown on the

23rd of September, and was executed at Tappan on the 3rd of

October of the same year.

André was tried by a board of fourteen

general officers, Lafayette, Greene, Stirling and Steuben being

among the number. He was declared to be a spy and condemned to

suffer the death of one.

His execution took place in the presence

of the army, on the summit of a low hill about a quarter of a

mile to the west of Tappan. A monument has been erected at

Tarrytown to the memory of John Paulding, David Williams and

Isaac Van Wart, the captors of Andre.

A monument to the memory of Williams has

been erected on the grounds of the old fort at Schoharie, he

having been a resident of Schoharie County for many years before

his death. The Corporation of the City of New York erected a

monument to the memory of John Paulding in the graveyard of the

little church on the Van Courtlandt Manor, about two miles west

of Peekskill. In 1829 the citizens of Westchester County erected

a monument at Greenburgh in memory of Isaac Van Wart. While

these men and their acts are kept in remembrance by the monument

erected in their honor at the place where André was captured,

the people among whom they lived also honored their act and

commemorated their memory by suitable monuments.

The Military School at West Point

Washington, mindful of the fact that a

large portion of his trained officers during the Revolution were

chosen from the ranks of foreign soldiers, because we lacked men

who had had military training, urged in his message of 1798 the

establishment of a military academy. Congress being then, as

often, very dilatory, nothing was done at that time toward

acting upon Washington's recommendation. In 1798, 1800 and 1801

some provision was made for the instruction of cadets, but it

was not until 1802 that the Military Academy can fairly be said

to have come into existence, and it led a very feeble life till

1812; in fact, there was not a single cadet at West Point at the

time of the declaration of war between Great Britain and the

United States.

Looking North from West Point

At this time Congress was willing to

act, and provision was made for two hundred and fifty cadets. It

was provided that admission to the Academy should be determined

by examination, which had not previously been required.

Major Thayer was made the Superintendent

of the Academy in 1817 and he held the position for sixteen

years. To him, far more than to anyone else, is due the credit

for the general plan of the school.

The usefulness of the Academy was fully

justified during the Civil War, for although only the merest

fraction of the officers engaged on either side had had any

military experience, a very large portion of those who achieved

eminence during the conflict owed their success to the training

they received at West Point. This fact is shown by the careers

of Grant, Lee, McClellan, Jackson, Sherman, Johnston, Burnside,

Beauregard, Hooker, Pemberton, Sheridan, Longstreet, Thomas,

Bragg, Halleck, Rosecrans, Early, Buel, Buckner, and many

others.

The Academy has grown continually in

equipment and in efficiency. There are now more than one hundred

fifty buildings of various kinds in use and Congress has

appropriated several millions for further improvements.

Kingston

Our state government was organized at

Kingston in 1777. It was there on the 30th of July, 1777, that

George Clinton was declared elected the first governor of the

state. Kingston received its first charter from Governor

Stuyvesant in 1661. Kingston was the first capital of the state,

and at the time it was made the capital had about twenty-five

hundred inhabitants, being the third city of the state in

population.

In 1776 the General Assembly of New York

changed its title to "Convention of Representatives of the State

of New York." The body appointed a committee to draft a

constitution for a state government and then adjourned to meet

in the city of New York on the 8th of July, but the appearance

of Howe before that date prevented the meeting. The convention

held short sessions at Harlem, White Plains and Fishkill, and

then adjourned to meet at Kingston, where they reassembled in

February 1777, and continued in session till the following May.

They met in a stone building that is sometimes called the

Constitution House and sometimes "Old Senate House." Here the

first constitution for the state of New York was adopted. John

Jay was the chairman of the committee that drafted it and the

work was mainly his. The draft of the constitution was submitted

to the convention on the 12th of March. It was very fully

discussed and was adopted on the 30th of April, 1777. The work

of drafting this constitution was so well done that we lived

under it for forty-seven years, very few amendments being made

during that time. This constitution was printed in pamphlet form

at Fishkill by Samuel Loudon, on the only press in the state to

which the patriots had access at that time. It is a matter of

some interest that this was the first book printed in the state.

Constitution House at Kingston

At the time of the advance of Sir Henry

Clinton, in 1777, Fort Putnam was not yet completed, and there

was no other fort at West Point on the west side of the river.

Fort Constitution was opposite West Point on what is now known

as Constitution Island. Forts Montgomery and Clinton were

opposite Anthony's Nose. Clinton easily made his way up the

river. With him was General Vaughn with a force of thirty-six

hundred men. All the vessels on the river were destroyed, and

the houses of prominent Whigs were burned. The expedition

reached Kingston on the 13th of October, 1777. A force was

landed and the city was burned, only a few stone buildings

escaping destruction. It was supposed that Clinton would go on

up to Albany, but for some reason he went down the river again,

and the surrender of Burgoyne a few days later made it

impossible for Clinton to hold any part of the river above West

Point.

Albany

This place was first known as Beverwyck

(sometimes spelled Beaverwyck), then as Willemstadt and finally

as Albany. It was incorporated as a city by Governor Dongan in

1686.

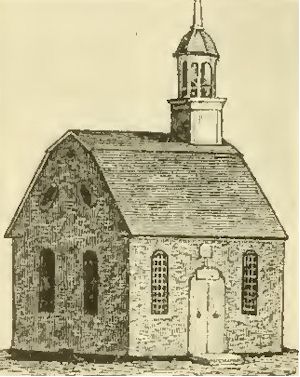

A little church was built at Albany

about 1657. In 1715 this was replaced by the one shown in the

illustration below. It was located in the open space bounded by

State, Market and Court streets. The following is from Watson's

"Sketches of Olden Times in New York": ''Professor Kalm who

visited Albany in 1749, has left us some facts. All the people

then understood Dutch. All the houses stood gable end to the

street; the ends were of brick, and the side walls of plank or

logs. The gutters on the roofs went out almost to the middle of

the street, greatly annoying travelers in their discharge. At

the stoopes (porches) the people spent much of their time,

especially on the shady side, and in the evening they were

filled with both sexes. The streets were dirty by reason of the

cattle possessing their free use during the summer nights. They

had no knowledge of stoves, and their chimneys were so wide that

one could drive through them with a cart and horses."

Ancient Dutch Church at Albany

Albany was the natural gateway to the

north and west. This gateway had to be held against the French

and Indians in the early days, and later against the British and

the Six Nations. From the earliest times Albany has been a place

of great importance. It is said to be the second oldest existing

settlement in the original thirteen colonies. In 1524 Verrazano

went up the Hudson, and not long after some French traders built

a fortified trading post on Castle Island. Hudson did not come

till eighty-five years later. At the time that the French first

came to the vicinity of Albany it would have been vastly more

proper to have spoken of America as the "Dark Continent" than to

have applied that name to Africa fifty years ago.

When Albany became a city in 1686 it was

second in population and resources to New York only, and hardly

second to it in importance. For a century and a half everything

to the west and north of Albany, save the little hamlet at

Schenectady, and the French settlements on the St. Lawrence, was

an unbroken wilderness.

In the early days not only the peace and

comfort, but the actual existence of Albany was dependent upon

the friendship of the Six Nations. This was very carefully

cultivated by the Dutch. Once, at a council fire, a Mohawk

sachem gave Albany the name of "The House of Peace."

During the French wars Albany was a

storehouse for munitions of war, and the rendezvous for troops.

It was one of the busiest places on the continent.

In 1754 a convention of colonial

delegates was held at Albany for the avowed purpose of renewing

treaties with the Six Nations, but also with the hope of

creating some bond of union between the colonies, the need of

which had long been felt. Seven of the colonies, New York,

Massachusetts, New Hampshire. Connecticut, Rhode Island,

Pennsylvania, and Maryland, responded to the call. Many very

able men were among the delegates, Benjamin Franklin being one

of the delegates from Pennsylvania. He presented a plan for the

union of the colonies, which, after much debate, was approved by

the convention, but nothing came from it directly, though no

doubt it aroused a train of thought which in time bore fruit.

James DeLancey was chosen president of the convention and made

an address to the Indians. The chief speaker for the Six Nations

was King Hendrick.

Albert Shaw says Albany has long been

one of the three or four chief law making centers of the English

speaking world.

Newburg

When at Newburg Washington occupied for

his headquarters a house built in 1750 by Colonel Jonathan

Hasbrouck. The house is now owned by the state, and is open for

visitors at all times. It contains many military relics.

While Washington made his headquarters

at Newburg, Generals Knox, Greene, Gates, and Colonels Biddle

and Wadsworth were at Vail's Gate, four miles south of Newburg.

They made their headquarters in the Ellison House, which is not

now standing. It was while he was at Newburg that Washington

received the famous Nicola letter, in which the writer went on

to say the troops were without pay, and that Congress was either

indifferent or helpless; that the form of government was weak

and that many thought it best to put all authority in the hands

of one man. He argued that republics were weak and that whatever

progress had been made was due to the army and not to the civil

government. This whole matter had been much discussed by several

officers in the army, and Colonel Nicola was selected to present

the matter and suggest that Washington become practically king

and ultimately assume that title. Nicola performed his task as

tactfully as such a task could be performed, perhaps, but its

effect upon Washington might easily be imagined. His reply to

Colonel Nicola is given here.

Washington's Headquarters at Newburg

|

Newburgh, May 22d, 1782.

Colonel Lewis Nicola.

Sir:-With a mixture of great surprise and astonishment,

I have read with attention the sentiments you have

submitted to my approval. Be assured, sir, no occurrence

in the course of the war has given me more painful

sensations than your information of there being such

ideas existing in the army as you have expressed, and

which I must view with abhorrence and reprehend with

severity. For the present the communication of them will

rest in my own bosom, unless some further agitation of

the matter shall make a disclosure necessary.

I am much at a loss to conceive

what part of my conduct could have given encouragement

to an address which to me seems big with the greatest

mischief that can befall my country. If I am not

deceived in the knowledge of myself, you could not have

found a person to whom your schemes are more

disagreeable. At the same time, in justice to my own

feelings, I must add that no man possesses a more

sincere wish to see ample justice done to the army than

I do, and so far as my powers and influence, in a

constitutional way, extend, they shall be employed to

the utmost of my abilities to effect it, should there be

any occasion. Let me conjure you then, if you have any

regard for your country, concern for yourself, or

posterity, or respect for me, to banish these thoughts

from your mind, and never communicate, as from yourself,

or anyone else, a sentiment of the like nature. With

esteem, I am sir,

Your most obedient servant, G.

Washington.

|

AHGP New York

Source: Stories from Early New York

History, by Sherman Williams, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons,

1906.

|